In the last 10 years, the primary consumer of log data shifted from humans to machines.

Software engineers still read logs, especially when their software behaves in an unexpected manner. However, in terms of "bytes processed", humans account for a tiny fraction of the total consumption. Machines, not humans, are crunching log data day and night to generate reports and run statistical calculations to help us make decisions. The insights derived from log data used to be post hoc, pull and episodic. Today, it is ad hoc, push and statistical.

Undoubtedly, Moore's Law and the advances in distributed systems design have made large-scale log processing and data mining accessible. However, many organizations, even with abundant financial and human capital, fail to turn their rapidly growing log data into actionable insights. Why can't they get value from their log data if all the pieces are available and affordable?

That's because legacy logging infrastructure was NOT designed to be "machine-first", and so much effort is wasted trying to make various backend systems understand log data.

The rest of this article explains why legacy logging infrastructure is ill-fit for the coming age of large-scale log processing and proposes the Unified Logging Layer as an alternative.

Most existing log formats have very weak structures. This is because we humans are excellent at parsing texts, and since we used to be the primary consumer log data, there was little motivation for log producers (e.g., web servers, syslog, server-side middleware, sensor devices) to give log formats much thought.

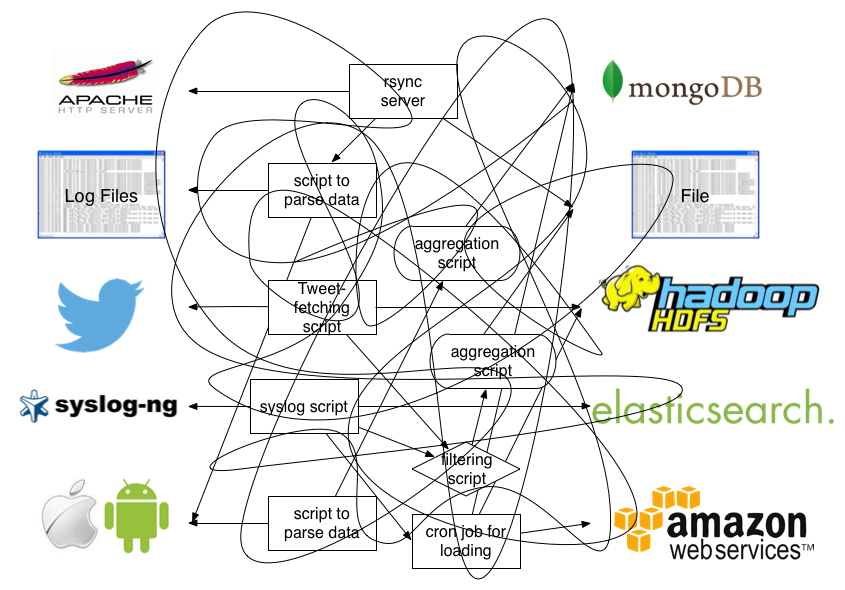

Arbitrarily formatted texts are terrible at analyzing logs because computers are terrible at parsing and extracting information from them. This is why the ability to write complex regular expressions is deemed to be a heroic skill, and so many throwaway one-liners are written to parse, extract and load data from logs. Many of you surely finds the following jumbled mess all too familiar:

Avoiding this chaos is simple, at least in theory: Define an interface that all log producers and consumers implement against. This is the first requirement for the Unified Logging Layer.

The specifics of the interface is less important that its existence, but several formats seem to be popular: JSON, Protocol Buffer, Thrift, etc. Here are a couple of criteria that you want to think about as you choose the interface:

Some interfaces are more rigid than others. For example, Protocol Buffer requires templates and versioning whereas JSON has no centrally managed templates or out-of-the-box versioning. More rigid interfaces are easier to manage but harder to evolve if the underlying data is evolving rapidly. More flexible interfaces can adapt to the changes better but can be harder to manage.

Remember that the Unified Logging Layer's key goal is to connect various sources of log data to various destination systems (NoSQL databases, HDFS, RDBMs, etc.). Hence, it pays huge dividends to choose an interface with ubiquitous support.

For instance, JSON might be slower than a custom binary protocol. But which database/data processing middleware supports such a custom protocol? On the other hand, with JSON, log data can be stored as-is in MongoDB, and while not very performant, there is JSON SerDe for Hadoop. Keep in mind that the goal is to unify your logging infrastructure, not to optimize prematurely for one-off use case.

The Unified Logging Layer must provide reliable and scalable data transport. If all log data were to go through the Unified Logging Layer, then it'd better be able to filter, buffer and route incoming data robustly. Thus:

The logging layer should provide an easy mechanism to add new data inputs/outputs without a huge impact on its performance.

The Unified Logging Layer should anticipate network failures and must not lose data when a network failure occurs.

If the Unified Logging Layer is implemented as a push-based system, it means that the logging layer must support retry-able data transfer (e.g. disk-based buffering). If the logging layer is implemented as a pull-based system, then, it is the log consumer's responsibility to ensure a successful data transfer (e.g., via offsets).

The Unified Logging Layer must be able to support new data inputs (e.g., new web services, new sensors, new middleware) and outputs (new storage servers, databases, API endpoints) with little technical difficulty.

To achieve this goal, the Unified Logging Layer should have a pluggable architecture into which new data inputs and outputs can be "plugged". Once a new data input is plugged in, no additional work should be required to send that data to all existing data outputs and vice versa.

For those with a CS background, pluggable architecture reduces an O(M*N) problem to an O(M+N) one: with M data inputs and N data outputs, there are M*N possible paths for log data. However, with a (well-designed) pluggable architecture, only M+N plugins need to be written to support M*N paths, and the cost of supporting a new data input or output is O(1) (= just writing a plugin for said input/output).

A strong emphasis on extensibility reduces the complexity of logging infrastructure and prevents the organization from accruing a large infrastructure debt.

The Unified Logging Layer is still in its infancy, but its strategic significance is already underscored by open source projects such as Kafka (LinkedIn's key data infrastructure to unify their log data) and Fluentd. The reader is strongly encouraged to start thinking how to evolve their organization towards building a Unified Logging Layer to make sure they can take full advantage of all the information buried in their log data.

Fluentd is an open source data collector to simplify log management.

2025-12-25: Drop schedule announcement about EOL of Fluent Package (fluent-package) 5

2025-09-04: Upgrade Guide for fluent-package v6

2024-08-29: Scheduled support lifecycle announcement about Fluent Package v6

2023-08-29: Drop schedule announcement about EOL of Treasure Agent (td-agent) 4

2023-08-29: Scheduled support lifecycle announcement about Fluent Package

2023-07-31: Upgrade to fluent-package v5

2025-12-25: Drop schedule announcement about EOL of Fluent Package (fluent-package) 5

2025-12-19: fluent-package v5.0.9 has been released

2025-12-09: Fluentd v1.16.11 has been released

2025-11-11: fluent-package v6.0.1 has been released

2025-11-06: Fluentd v1.19.1 has been released

2025-10-08: fluent-package v5.0.8 has been released

2025-09-12: Fluentd v1.16.10 has been released

2025-09-04: Upgrade Guide for fluent-package v6

2025-08-29: fluent-package v6.0.0 has been released

2025-08-06: Fluentd v1.19.0 has been released

Want to learn the basics of Fluentd? Check out these pages.

Couldn't find enough information? Let's ask the community!

You need commercial-grade support from Fluentd committers and experts?

©2010-2026 Fluentd Project. ALL Rights Reserved.

Fluentd is a hosted project under the Cloud Native Computing Foundation (CNCF). All components are available under the Apache 2 License.

The Linux Foundation has registered trademarks and uses trademarks. For a list of trademarks of The Linux Foundation, please see our Trademark Usage page.